Southern Blue Laws, Uzbek Hospitality and 20 Hours on Amtrak’s Silver Meteor

Fresh bread. Cubes of cooked lamb. Beef sausage. Not what I expected to eat on an overnight Amtrak ride up the Eastern seaboard.

Just weeks after Amtrak suspended dining car service on East Coast trains — supposedly a response to Millennials preference to dine alone — I nonetheless enjoyed one of my most unique Amtrak dining experiences: a Central Asian feast with an Uzbek truck driver.

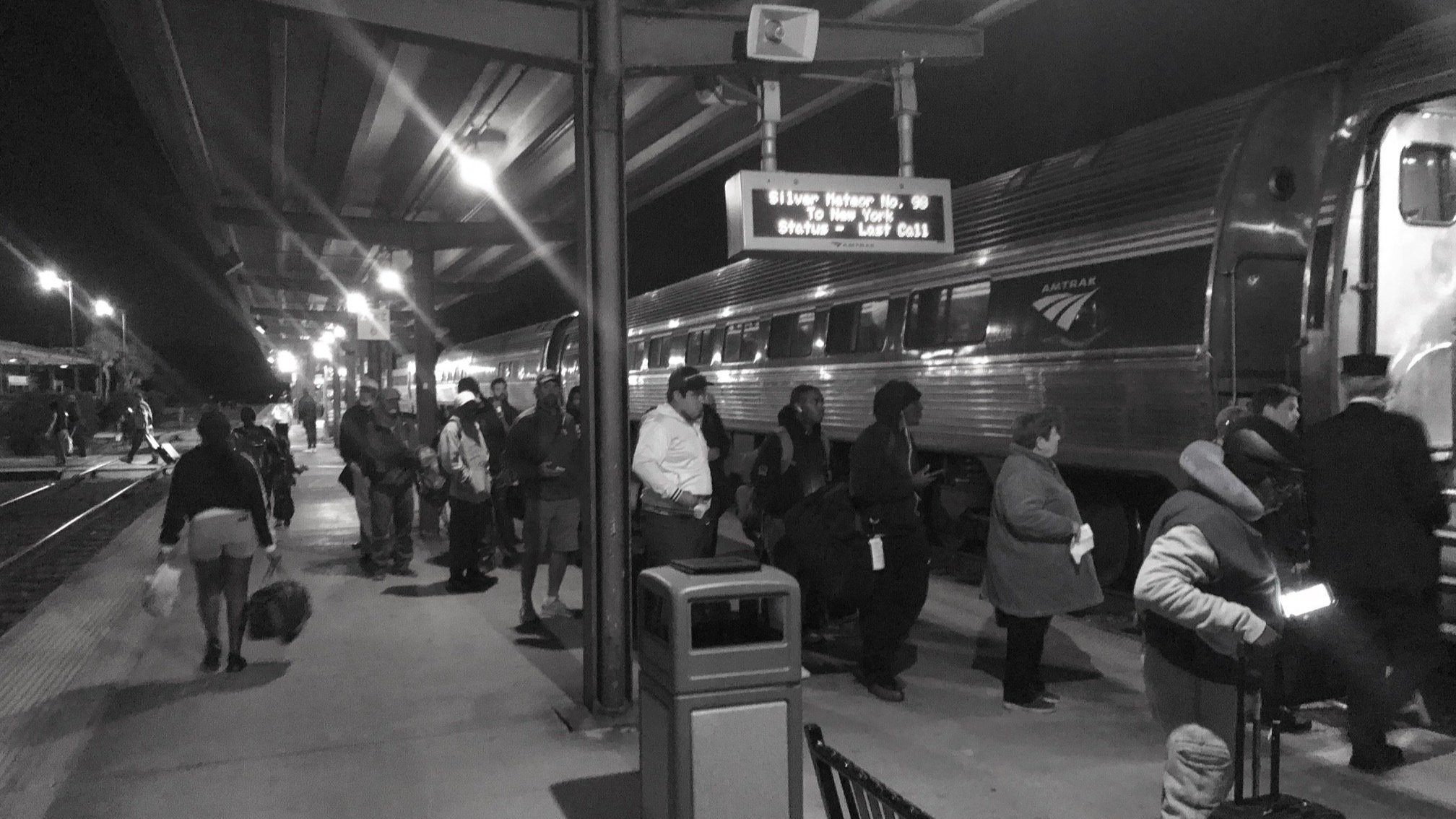

My trip began in Deland, Florida, where my parents dropped me off en route to Orlando Airport, 60 miles to the South. We had just spent the weekend at family gathering in Palm Coast. With most relatives leaving the Hammock Beach resort on Sunday of Veterans Day weekend, I seized a rare opportunity to spend 20 hours traveling home to New York City aboard an Amtrak train. My Monday morning arrival in Newark would still gave me time to enjoy the holiday before returning to the office on Tuesday.

Like much of Florida, the Deland station is surrounded by dense greenery, with patches of water running parallel to the streets. To pass the time before my train, I took a short walk, seemingly an anomaly here, as there are no sidewalks. Afraid of snakes and gators, I didn’t want to walk on the muddy grass, but I had to step into it for every passing pickup truck.

Amtrak trains are always full of interesting people, and I could tell at the station that this would be no exception. Bald and middle aged, with glasses strapped around his head with a band, the fellow passenger walked by me outside the station chain-vaping and told me — in a tone that told me he might be slightly mentally challenged — that the train was running about ten minutes late. A few minutes later, inside the station, he told me all about the cold weather up north, chance of snow tomorrow. He was going to DC but raised in Jersey, so he’s used to the cold. I hoped I wouldn’t be seated next to someone so talkative, and thankfully, even though we boarded sequentially, I was not.

I was instead assigned an aisle seat next to an Asian man roughly my age on the west side of the northbound train. With the sun dipping low, he kept the curtains closed and watched comedy videos on his tablet. I strained to read the scribbled destination on the tag above the seat — hoping he would leave before nightfall and give me two seats to myself — but could not make it out. Our only interaction in the first hour of the ride was his telling me in broken English that I should feel free to use the outlet along the window to charge my phone.

I was eager to grab a beer in the cafe car, but forced myself to do some reading first. As the train pulled away from Deland, I began the prologue to William Langland’s narrative poem Piers Plowman, one of the more difficult readings for my medieval travel writing class.

Fresh air stop in Savannah, Georgia, aboard Amtrak’s Silver Meteor. Photo by Vincent Gragnani.

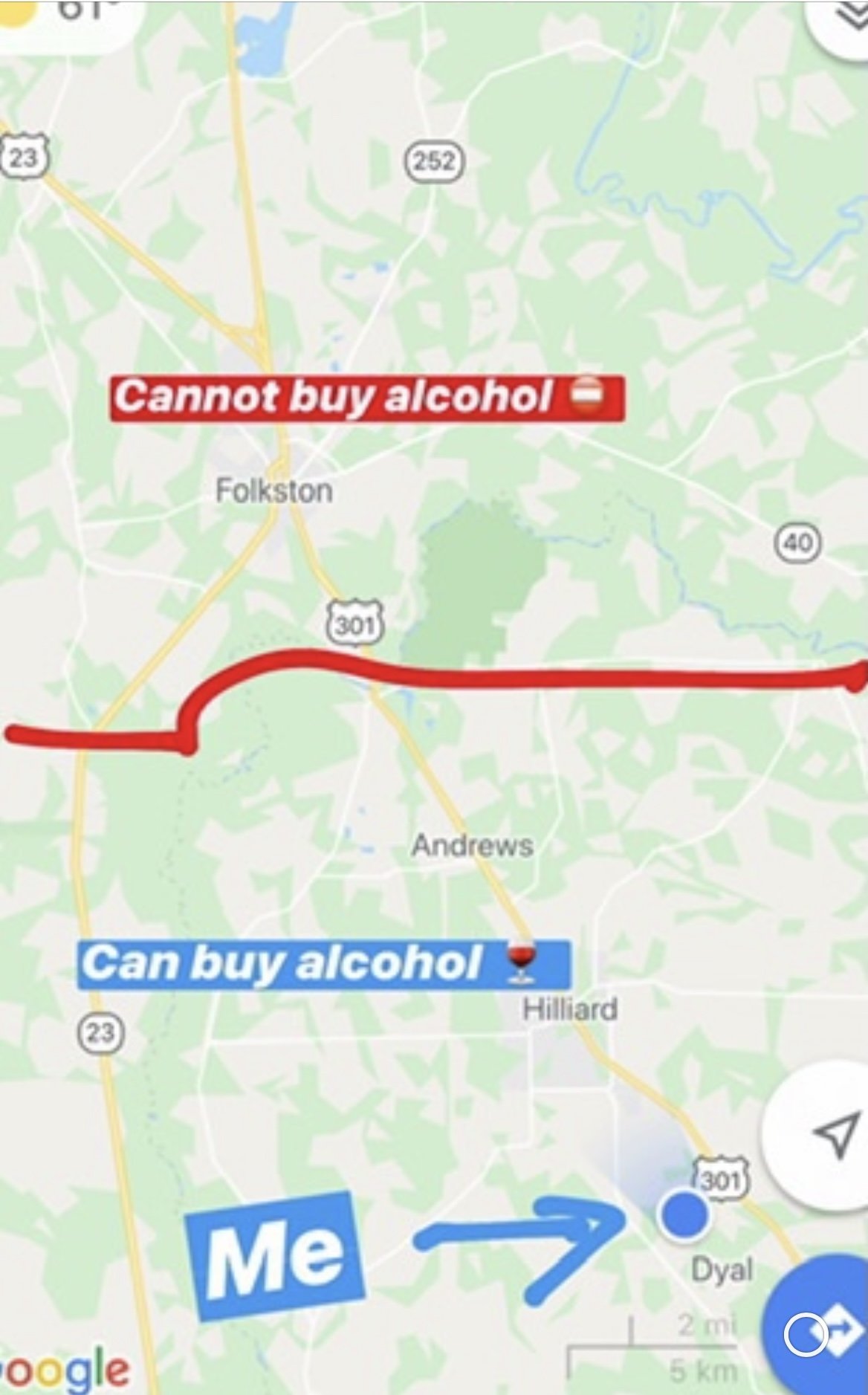

After an hour or so of trying to read, I made my way to the cafe car, where I envisioned drinking Yuenglings all evening and striking up conversations with fellow train travelers who also enjoyed their brews. I was shocked to hear the attendant announce that alcohol service would end as we crossed into the Carolinas, where the sale of alcohol was prohibited on Sundays. Thankful that I had grabbed a sixpack at a gas station on my pre-departure walk, I nonetheless ran up to the attendant and ordered two Yuenglings. He told me that even though some counties allow the sale, it would be too difficult for Amtrak to determine this as it traveled along, so this would be my final alcohol purchase on this ride.

A few hours later, resting in my coach seat after the Yuenglings, I was preparing to return to the cafe car for an evening snack, when the man next to me pulled a yellow canvas back from the overhead rack and motioned toward the cafe car. Two minutes later, I went back myself, and when I saw him alone at a table for four, he motioned for me to join him. My intention was to have a seat across from him and order a Digiorno cheese pizza — but he had another idea.

He pulled from his bag a long towel and placed it between us on the table. He unfolded a metal fork and placed it in front of me, and unfolded a metal spoon and placed it in front of himself. He held up a round loaf of bread, with dark sesame seeds in the center. “Flour, water, salt,” he said as he offered me to break a piece.

One by one, he pulled food out of his bag and held each up for me to see. A jar of tomato and eggplant caponata. A jar of herring in olive oil. A Tupperware container of cubes of cooked lamb. A large piece of sausage wrapped in plastic, “100 percent beef,” he said, slowly and deliberately.

His limited English kept our conversation minimal. But I learned he was originally from Uzbekistan, now a truck driver living in Pittsburgh, on his first train in the United States, going from Orlando to Pittsburgh via a stop in Philadelphia. The ride would take more than 30 hours. He wished he had driven, as that would have taken only 14 hours. He was surprised at the cost difference between coach and a sleeper on Amtrak — $160 for coach vs several hundred dollars for a bed. He was proud of his home country, especially the bread that is baked there. He showed me some YouTube videos of bakers baking bread Uzbekistan. He encouraged me to watch the videos, and to make my own visit someday.

Between each bit of conversation, he encouraged me to take more food — more caponata over bread, more beef sausage, more lamb.

He handed me a can of sprats in tomato sauce. “Do you like this?”

“I am full, thank you,” I said, patting my stomach.

“If you like it, take it,” he said. I accepted.

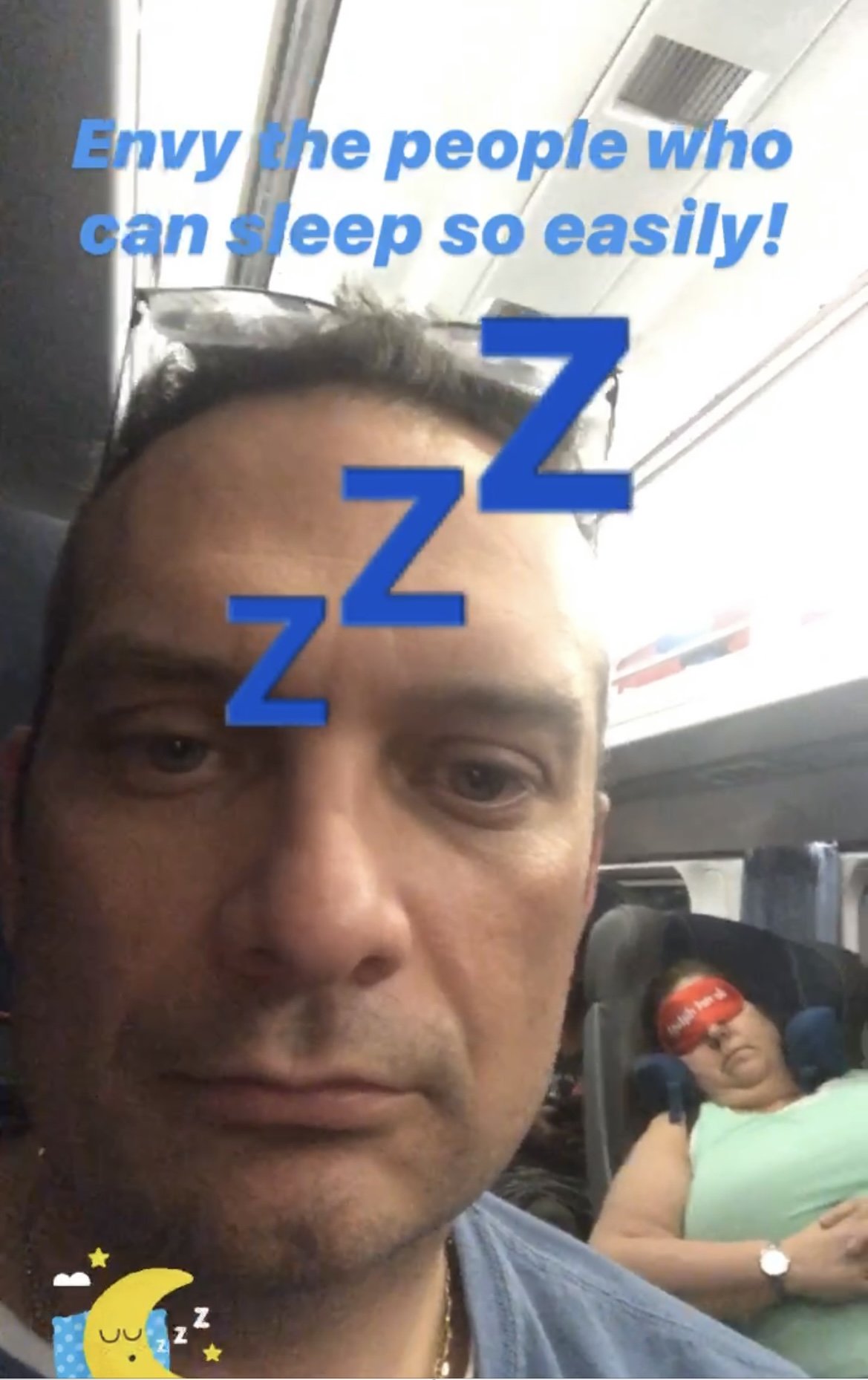

After dinner, we returned to our seats, where I attempted to sleep as the Silver Meteor made its way through North Carolina and Virginia.

Sunrise aboard the Silver Meteor, November 2019. Photo by Vincent Gragnani

The Uzbek truck driver and I never exchanged names, but we wished each other well as he de-trained in Philadelphia, where he would have an 3-hour layover before continuing on to Pittsburgh.

I remain grateful for his hospitality and his eagerness to share his food and images of his native country. I thought of him as I worked on my final paper for my medieval travel writing class, an analytical essay on travel and hospitality among Muslims in medieval Central Asia.

Even though I missed the Millennial generation by two years, I am close enough to speak as one and tell Amtrak that enjoying conversation with fellow passengers — even through a language barrier — is one of the joys of train travel for people of all generations.