Night Train to the Top of the World, from Stockholm to the Arctic

More than 100 miles north of the Arctic Circle, our Vy train to Narvik climbed an other-worldly landscape of lakes, rivers and waterfalls, dotted with cabins painted in Scandinavia’s iconic Falu red.

I was thousands of miles from home, and I felt as if I were on another planet. Population and vegetation were sparse as we climbed both in latitude and altitude, crossing through the Scandinavian Mountain range that forms the border between Sweden and Norway.

***

I have logged more than 40,000 miles by rail, and love trains so much that I’ve made slow train travel the subject of my master’s capstone. I have always been intrigued by the Arctic, drawn to the northern reaches of Scandinavia, Canada and Alaska when looking at maps or social media feeds, longing to someday see the Northern Lights. And for 24 hours in mid-October, I had the privilege of bringing these two interests together with a 637-mile train trip from Stockholm, Sweden, to Narvik, Norway.

If you had told me four months prior that October would bring me a train ride to the Arctic Circle, I would not have believed it. My initial plans for this Scandinavia trip were limited to a long weekend staying with family in Southern Norway, followed by a train ride — of course — to Bergen.

When we decided to instead begin the trip in Stockholm, I looked online for scenic train rides in Sweden and found this route — and knew I had to take it.

After 48 hours in Stockholm with our cousins, my brother Michael and I arrived at Stockholms Centralstation — a 151-year-old transportation hub that draws 200,000 visitors every day — with about 45 minutes to spare, my bags a little heavier than when I first arrived in the Swedish capital.

Our sleeper train would take us through Swedish forests, over steep mountains and down to the Norwegian port city of Narvik, where we would catch a 4-hour bus ride even farther north to Tromsø, the third largest city above the Arctic Circle.

This was exciting. That moment waiting at the train station may not have been more thrilling than other parts of a trip that would include beautiful walks in Stockholm’s Gamla Stan, hiking and boating with family in Southern Norway and seeing the Northern Lights dance over remote Finland for two hours. But in the planning process, when I realized I could take a train to the Arctic, it was like a distant dream suddenly becoming accessible. And now it was actually happening.

I grabbed one last cardamom bun at Stockholms Centralstation — my fourth in 48 hours — before we boarded. I had always associated cardamom with Middle Eastern food, but Sweden and Norway consume 18 and 30 times more cardamom than the global median, and cardamom buns were everywhere in Stockholm. Not knowing where I would find one again, I couldn’t resist one more.

When the train rolled in to the station, we found our car and boarded, joining a crowd of passengers from other parts of the world. I heard Italian, Chinese, and a lot of non-native English.

We had booked a couchette, a small space for six people, two benches facing each other by day, three beds on each side by night. I was hoping we’d have the space to ourselves, but we had the next best thing: just one other passenger, a quiet youngish man in a striped t-shirt and a baseball cap who had a bunk at the very top.

Mike and I didn’t stay long in the couchette. As soon as the attendant checked our tickets, we headed to the dining car, where we could sit at a table and enjoy some Bottenvikkens brews from northern Sweden and be around other passengers.

There was not much to see outside under the cover of darkness, though at Uppsala, I did my best to take a photo of the steeple of the cathedral, the seat of the primate of Sweden and site of coronations of new kings of Sweden. It is on my list for a future visit.

For dinner, I couldn’t pass up the most unique dish — reindeer stew with potatoes, mushrooms and lingonberries. Other offerings included folded flatbread with fried egg and Jokkmokk-sausage, and classic Swedish shrimp sandwich. Each boxed dinner bore the words “We proudly serve food made from scratch in Luleå.”

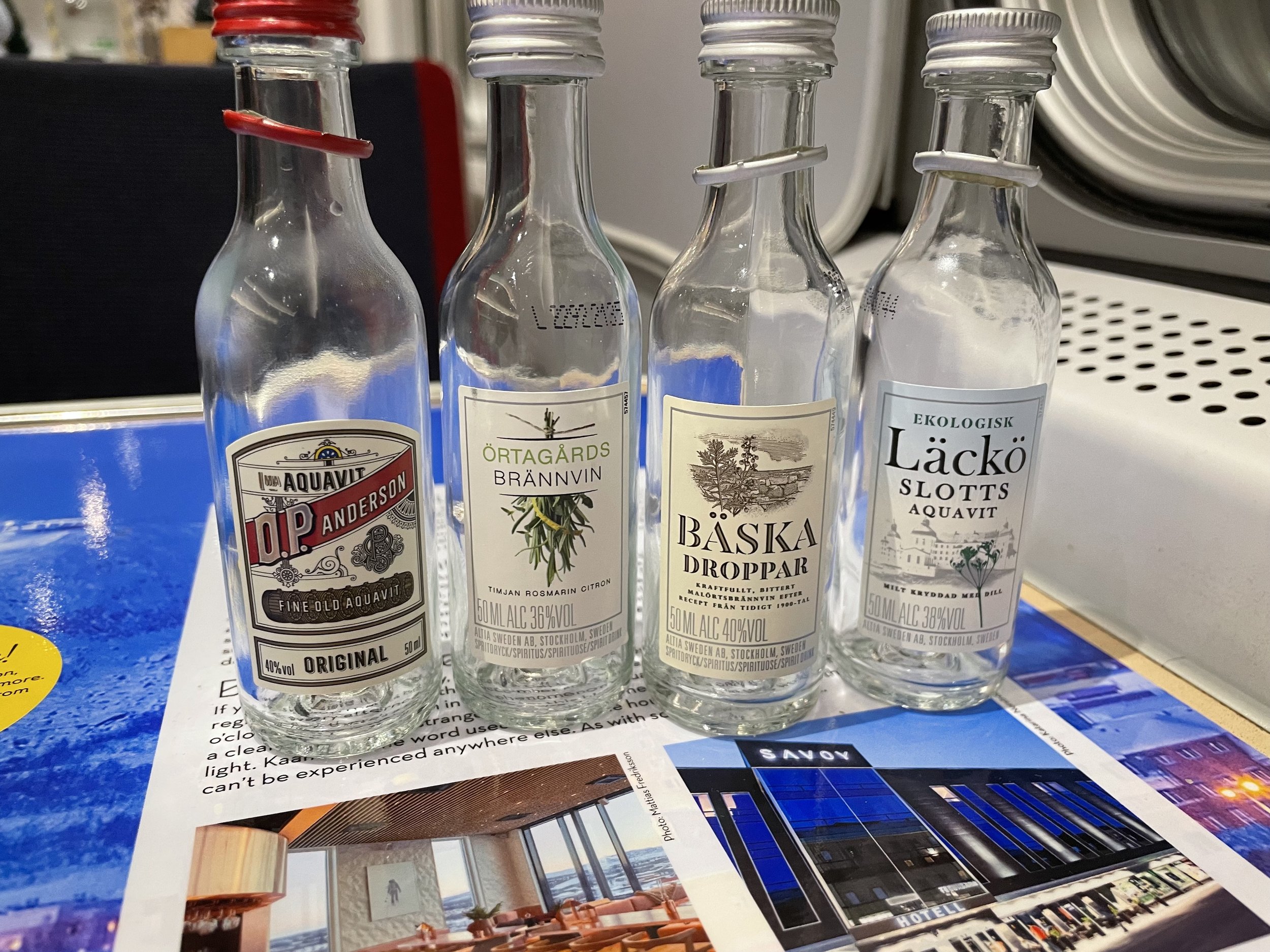

After dinner, I broke into the sampler pack of aquavit that I had purchased at the liquor store in the Åhléns department store in Stockholm. One after another, we split four tiny bottles, each one with a different combination of flavors, including dill, caraway, rosemary, citrus, cumin, anise, sherry and cinnamon. I split each between two glasses, and as we would do throughout the trip, Mike and I toasted with the Scandinavian “skål” first tapping each other’s glass, then tapping our own glass to the table as a toast to the house before taking the first sip.

As the clock neared 11 pm and we prepared to head back to our couchette, the conductor asked what we were drinking, and when I showed him our mini aquavit bottles, he told us this was a restaurant and that we could not drink our own liquor there. We were grateful that he admonished us at 11 pm and not 6 pm, as we were finished anyway for the evening.

Back at the couchette, we made our beds as quietly as we could, knowing that someone else was above us. I would have hated to be in his position, so close to the ceiling. I slept relatively well, waking up every so often to peek outside to see if I could see the Northern Lights.

I knew that the restaurant car would open at 5 am and, wanting to be among the early risers, I got up at 5:30 to head down there. The train was stopped at the Älvsbyn station, and as I made my way to the restaurant car, I found an open door and stuck my head out for fresh air. There I met a train attendant who told me we were stuck for a bit, awaiting information on when we could proceed. I sat and had my tea, texting with my mom and waiting — and waiting — and waiting.

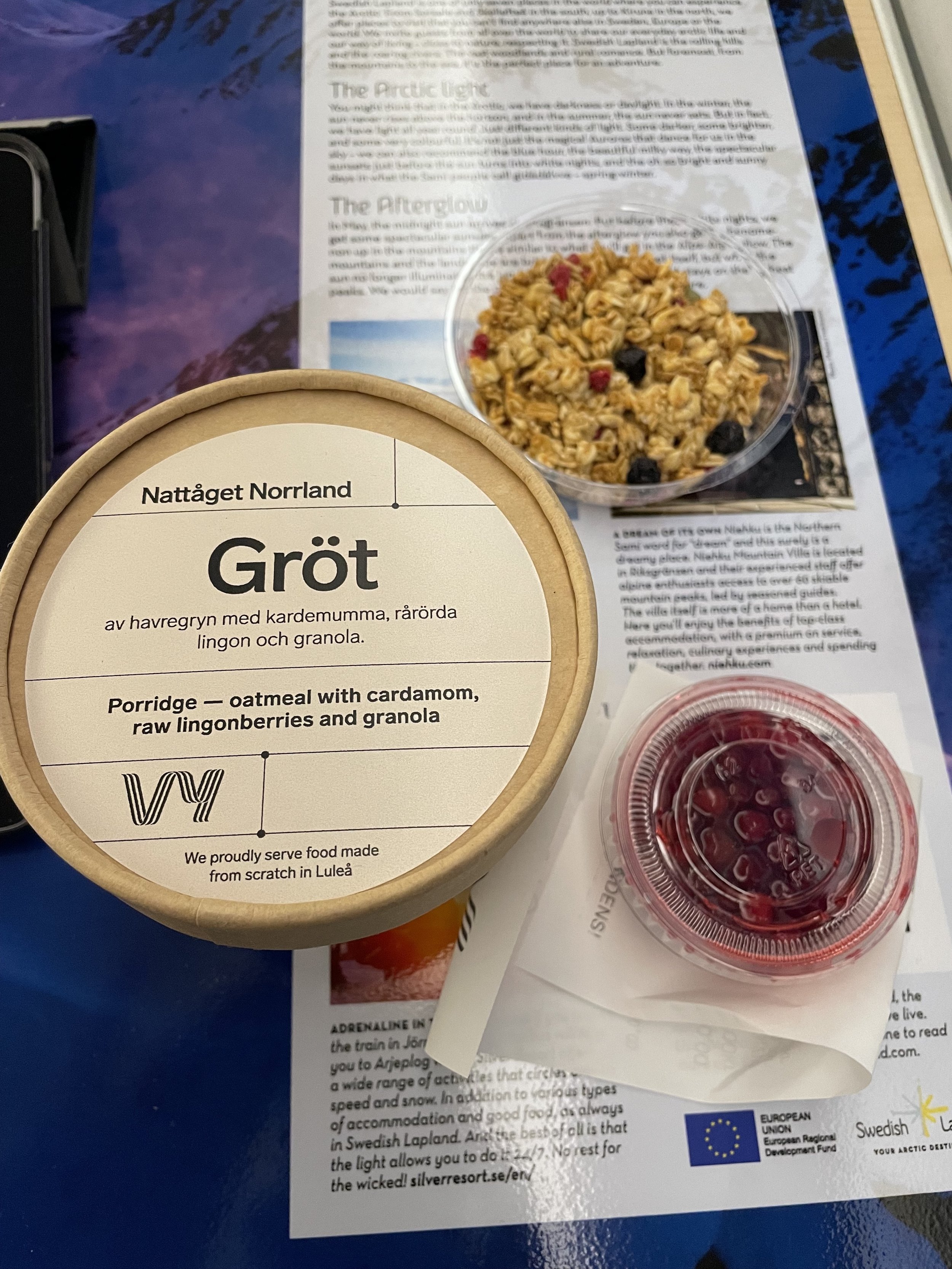

I had oatmeal with cardamom, granola and lingonberries, and we waited some more. After an hour of “we will know soon,” we were told that due to track problems ahead, we would have to take a bus to Boden and board a new train there, not arriving in Narvik until after 5 pm, long after our bus — and a final subsequent bus — to Tromsø would have departed.

Mike and I gathered our stuff, and we were among the first to step off the train and into the tiny station, which did not have wifi, or anything but a bathroom. At around 9:30 am, a bus arrived to take us to Boden. We were not far from the northern reaches of the Gulf of Bothnia that separates Sweden from Finland. Our bus meandered through Swedish forestland, the first of many, many, many miles of it that we would see in the coming hours.

I was disappointed to learn that the train we would board at Boden was a day train, lacking many of the amenities of our night train, namely, my favorite one, the restaurant car. We could buy food and drinks, but with no communal place to eat, we would have to take them back to our seats. We were assigned two window seats, one behind another.

The portion of the trip north of Boden is on a stretch of track known as the Iron Ore Line, which connects Luleå, Sweden, on the Gulf of Bothnia, with Narvik, Norway, on the North Sea. The line was completed in 1903 to bring iron ore from Sweden to Narvik. Trains on this line have run on electric power since at least 1923 (while the vast majority of track in the United States remains non-electrified a century later). The line still transports iron ore from Kiruna, Svappavaara and Malmberget, as well as non-ore shipments of food to the north and fish to the south.

Watching the forests pass us by, I tried to detect changes as we moved north into a different climate. Most of the route seemed to be a dense mix of birches that were losing their leaves — a few weeks ahead of the brilliant yellow trees in Stockholm — and conifers.

But as we neared the Arctic Circle, the birches had lost all their leaves, and they seemed to be fewer in number. The conifers, too, were fewer, as the dense forests grew more sparse.

What was also sparse here — noise. I like to chat with other people on trains, but this car was silent. We seemed to be the only Americans on board. Other passengers included a young British couple, a middle aged Scottish couple that we would bump into outside a pub in Narvik later that night, a group of about eight Asian people, and the rest seemed Norwegian, Swedish or German. A walk to the coach area adjacent to the bistro was a much different story — a group of Italians were talking loudly and fast. I loved to hear it and wished we were seated with them.

***

Crossing the Arctic Circle was not as eventful as I expected. I had marked the spot on my Google maps a couple weeks prior to the trip so that I would know the exact moment we crossed. We passed a sign marking the spot — Polcirkeln — just before the mark on my phone. In any case, I had never before been above the Arctic Circle, so it was an exciting moment — and we still had miles and miles and miles to go.

Most of my long-distance train travel has been in the United States, where I marvel at the vast expanses of open space. With an average density of 35 people per square kilometer, the United States is half as dense as Europe, which has 73 people per square kilometer. However, for this trip, I was traveling through countries far less dense than even the United States: Sweden has 23 people per square kilometer, and Norway has only 17, about half the density of the United States. The land here was wide open.

As we pressed farther north, the train did not take on many new passengers, meaning the train, too, was not densely populated. We mostly discharged passengers, especially at Kiruna, a mining town in Swedish Lapland with about 23,000 inhabitants.

The landscape continued to change. The forested hills of southern Sweden were replaced by flatter land, shorter trees, and lots of lakes. In the distance, we could begin to see the Scandinavian Mountains, the range that runs the length of the border between Sweden and Norway, which we would soon be crossing.

After Kiruna, we could really spread out, which for me meant that I could move from the left side of the train to the right to take photos and video. It was here that we engaged in conversation with some fellow passengers.

Lars, from Bavaria, was going to Abisko, where he planned to take two 20-km hikes before continuing on to Lofoten for a few days, and then down to Bodø by bus and by train to the south, to be possibly followed by a ferry to Denmark. He was clearly a fan of traveling by land and sea — and had the time to do so.

Ann, from Aarhus, was now living in Tromsø, traveling back north by land because of the detrimental effects air travel has on the climate. She was frustrated by how long and expensive the ride was, and how governments fell short of making it easier for people to make the right choices. Our delay would make her long trip longer and more costly for her. I shared her frustration, but reminded her that much of Europe is light years ahead of the United States when it comes to climate-friendly travel options.

For all of its faults, social media can be a great way to maintain a connection with people I have met on my travels. I still follow students I met at a bar in Freising, and fellow travelers whom I met at Piana Vyshnia, or the Drunken Cherry, in Lviv. So, I asked Lars and Ann if they were on Instagram, so that I could follow the rest of their journeys. As a result, we were all able to swap stories about seeking reimbursement from the rail company for our delay and photos from our subsequent travels.

I can’t say enough about the last few hours of that train ride. After Abisko, the train began to climb the Scandinavian mountains, reaching a height of about 1,700 feet above sea level, alongside mountains that towered much higher.

The word tundra always connoted some distant barren landscape, something one finds in a nature book or a textbook. Now, I was riding through it.

Mosses, lichens and low shrubs offered some color against the rugged, exposed rock. Birches that had long lost their leaves appeared here and there. If not for the sporadic red and gray cabins, I would have thought that a wildfire had recently wiped out this area.

To be more specific, we were crossing through a biome known as the Scandinavian Montane Birch Forests and Grasslands, a tundra ecoregion that spans much of Norway, as well as parts of northern Sweden and Finland.

Though I couldn’t identify them at the time, I later learned that many of the low shrubs I was seeing was likely a mix of crowberries, reindeer lichens, cloudberry, bilberry and wolf’s bane. And yes, the trees were largely downy birches — I could easily identify birches by their white bark — that would grow no taller than 2 to 3 meters, but also may have included aspen, Scots pine, juniper, grey alder, rowan, goat willow and bird cherry.

We passed many alpine lakes that would soon freeze over under the coming polar night. Under the surface likely swam char, trout, tench and minnow.

In Sweden, the lakes all ended in -jávri (Báktájávri, Loktajávri, Vássejávri) the word for "lake" in the Northern Sami language. Once we crossed to Norway, they ended -vatnet (Brudeslørvatnet, Hansenvatnet, Telegrafvatnet) Norwegian for “the water.”

The sun hung low near the horizon, and I was grateful that despite the delay, we were not passing through this stretch in darkness. As I publish this in early November, sunset in Kiruna is 2:26 pm. On December 10, the sun will set at 11:48 am, and not rise again until 11:25 am on January 2.

In Narvik, the sun remains below the horizon from December 6 to January 7.

As we continued westward toward Norway, we hugged the side of mountains, going through several tunnels and snow sheds. Across the valley, I could see waterfalls, like ribbons spaced out on the side of the mountains. I spent much of the last hour or so in the back of the train, where I had a lot of space to myself to open a close windows on either side, and take a lot of video out of the left, right and rear of the train.

We made several stops in remote towns I could neither pronounce — Låktatjåkka, Vassijaure, Katterkåkk, Riksgränsen — nor imagine living in.

We crossed the Sweden-Norway border inside a tunnel, with the colors of the Swedish flag painted inside, suddenly changing to the colors of the Norwegian flag.

The line from the border to Narvik is known as the Ofoten line, and it brought us from an elevation of 1,700 feet down to sea level over the course of 27 miles, as we made the final stretch to our destination.

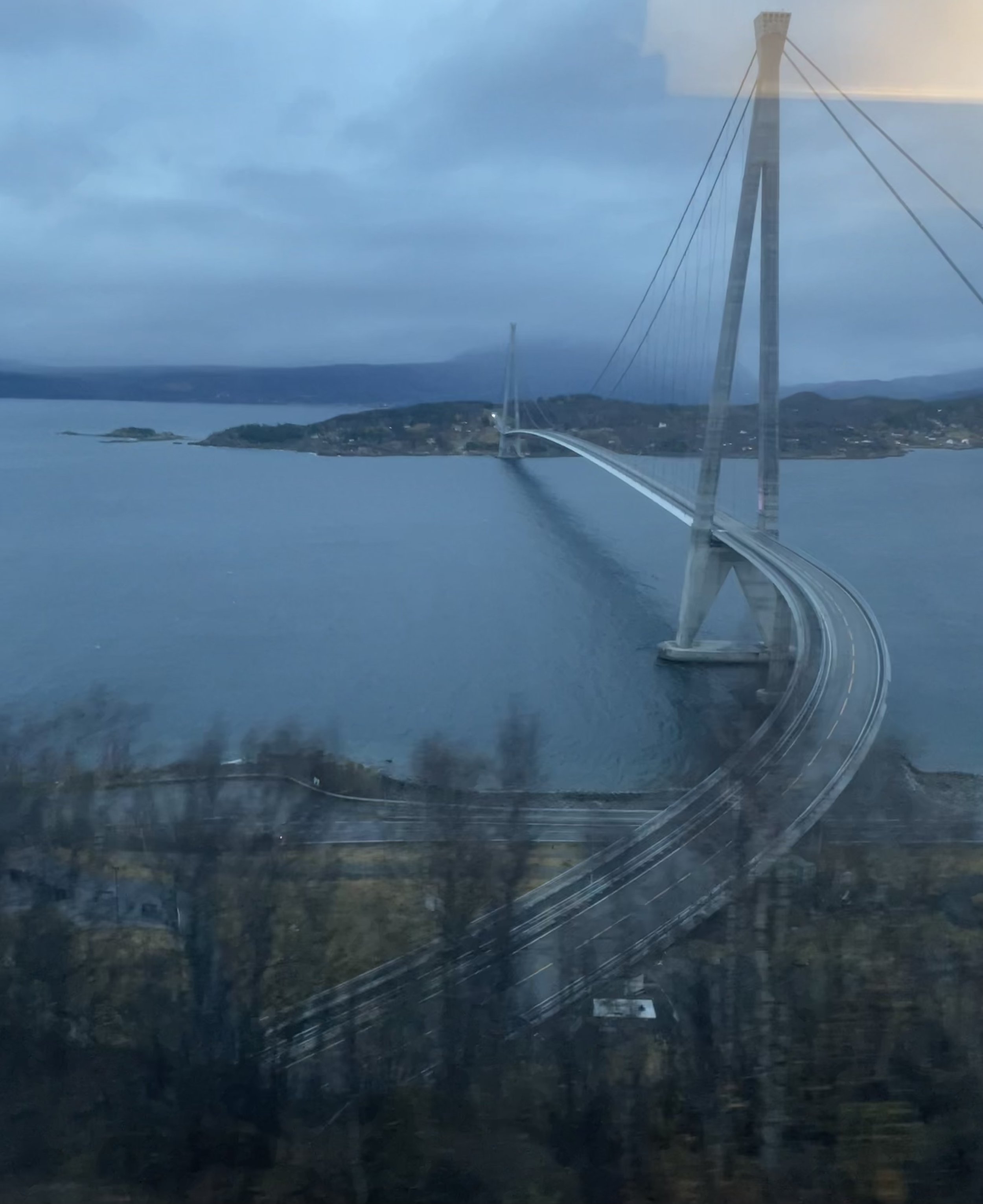

Soon, we could see a body of water below, the Rombaken, a 12-mile long fjord that was the site of several naval battles during the 1940 Battle of Narvik. The fjord branches out from Narvik’s Ofotfjorden. As we passed the massive suspension bridge that connects Narvik to Øyjorda across the fjord, we knew it was time for us to gather our bags, say farewell to Ann — with the chance we might see her on our predawn bus ride 12 hours later — and disembark, 637 miles from Stockholm and 130 miles above the Arctic circle.

At Narvik, we walked a half mile through a cloudy mist to the Scandic hotel. At nearly $200, it was the most expensive place to stay, but it was also closest to the bus station, it had a sky bar, and I was fairly confident it could be reimbursed by either the rail company or my credit card insurance.

It didn’t disappoint. The sky bar was amazing, with a nearly 360-degree view of the city. I can’t imagine being there to see either the Northern Lights or the midnight sun. But in our case, it was a cloudy and drizzly night, without much to see in the sky, but the view of the town was nonetheless fascinating.

After a drink and a massive charcuterie board, we left for Narvikguten pub, making a small loop up a hill to see what we could of the full moon. As we entered the pub, we ran into a Scottish couple from the train. I felt bad that they didn’t stick around, saying the prices were “too dear” for them, and that their pounds were especially weak these days. They were there just to check out the Arctic, heading back and continuing on to Spain after.

We took seats at the bar, realizing quickly that not food would be served there. Into our second beer, we decided that dinner was not entirely necessary after the charcuterie board. We struck up a conversation with the guy next to me, Gus, originally from Oslo and now living in the north with his fiancé. He was a bartender at the bar, drinking there on his day off, stepping out occasionally for a hand-rolled cigarette.

It was interesting — and refreshing — to hear his impressions of Americans. He saw a disconnect between Americans’ personalities and our politics. We are a welcoming people, he said, based on the conversations he had with Americans on all sides of the political spectrum. But if you judged us based on what you saw in the news, what would you think, I asked? I’d think you were absolutely out of your minds crazy, he said.

During our conversation, our bartender handed Gus two buttons, meant for Mike and me. They bore the name and logo of the pub. They said it was their stamp of approval on us as visitors, and that they welcomed us back any time.

After three or four or more beers, we called it a night, returned the to sky bar for a nightcap and a bag of chips — and then turned in, alarms set for 415 am to make our 5:30 am bus ride, an additional four hours to the North.